Orcs have been a staple of tabletop role-playing games (RPGs) since the beginning in the 1970s, adapted from Tolkien's works. Most recently, this has been highlighted by the 2024 edition of Dungeons&Dragons that makes playing an orc a core option for players (replacing the half-orc).

There has been a lot of controversy as well over what orcs represent, particularly over bioessentialism and/or a simplistic nature to their evil. As this essay makes clear, however, orcs don't represent one concept or even five. There are dozens of differing visions of orcs. A critique of one author's take on orcs might be completely valid, but it doesn't necessarily apply to all other versions.

As with any mythology, one should ideally understand the archetypes of orcs before using them in a new game, setting, or campaign. In Tolkien, orcs are also called goblins and though short, they are clever, advanced, and a major threat to the whole world. In early D&D, though, orcs and goblins split into different beings -- and both are more like primitive threats of the lowest level. In later games and editions, though, orcs have been reinvented as bigger -- alternately either hulking but dumb brutes; or a warrior race like Klingons from Star Trek.

As an alternative to not having orcs, this essay looks into the range of what orcs have been and can be. The idea is to understand the archetype better, and to suggest some different ways to use orcs in RPGs in interesting ways. For most of this, I will try to present orcs as they are portrayed, leaving discussion of social issues for the conclusion.

Literary tropes and meaning are even trickier in tabletop role-playing games than in static media like books and movies, because everyone's game is different. A role-playing game can write in the option of playing an orc or half-orc, but it can look very differently in play. One player could make an orc character who is a shallow collection of stereotypes, while another makes a character with many layers of depth. Plus there are hundreds of different published RPGs with their own interpretations. Even so, there are likely some commonalities that they are playing from.

To help guide understanding the differences, this essay groups the most common conceptions of orcs into four broad categories:

As with any interpretations or tropes, this is a shot in the dark at best. Even if the categories work, individual interpretations will vary within and between these.

These four all have some similarities, but also enough differences in traits that they can be distinguished. These categories are broader than stereotypes of a single group of real peoples, and can be flexibly applied with minor cosmetic changes. For example, the Warcraft games have human forces who have European-like style and architecture. One could instead have a game setting focused on a Chinese-themed human fantasy nation, where the orcs are barbaric invaders from across the sea. In that setting, Warcraft-like "warrior race" orcs could easily evoke images of invading Europeans, without any major changes to the archetype. The themes of orcish invaders depend on context.

One can have problems with some or all of these archetypes. However, it is important to understand that any archetypes rarely disappear, and certainly not quickly. However, they can be changed and reused in different ways to different meaning. The variety of different interpretations of orcs means that going forwards, gamers can pick, remix, and re-interpret orcs in new ways that change the baseline of what someone thinks when they say "orc".

There is a broad critique that any innately evil beings like orcs aren't truly responsible for their evil, because they don't have a choice. This suggests that fantasy violence should only be killing beings that choose evil, like Nazis or cultists or similar.

This is simplistic about choice, though. Even with free will, someone can be raised in vile beliefs and/or preyed upon - like the boy Jojo who ignorantly idolizes Hitler in "Jojo Rabbit". Further, someone could have joined up because of circumstance, even though they quietly oppose the cause - like Oskar Schindler who was technically a Nazi party member, but secretly worked against the Nazi goals. In real life, many cultists have later escaped the cult and gone on to very different lives.

In the real world, there is no guilt-free killing of any group of human beings. However, RPGs are not in the real world. Even RPGs in historical or modern-day settings are still fiction, not reality.

In short, it can be simple fun to kill monsters in D&D, or storm troopers in Star Wars, or cultists in Call of Cthulhu. This "pew pew zap zap" fighting doesn't necessarily encourage the players to go kill people in the real world. Instead, slaying monsters can symbolize taking on challenges in other ways. The defense of this is less in exactly what the monsters are, and more in what the fantasy is about.

This is not to say that fantasy and fantasy evil is meaningless, though. Effective monsters always represent some real-world evil. Tolkien's fantasy stories had deep lessons for real life, that many people drew inspiration from. That includes his down-to-earth heroes and also the evil orcs that embody many wrongs -- including war but also the destruction of forests for factories.

Later game designers and authors changed the details and context of orcs, so they may represent different evils than Tolkien. Of course, RPGs are games, not moral treatises. No one has to define exactly what sort of evil orcs represent in their game, but it can be interesting to think about for those who are interested.

Fantasy orcs need not represent the same evil as Tolkien's orcs, but they can represent many others. For example,

In the following timeline, I roughly categorize the interpretation of orcs in each source, but most of those are going to be wrong depending on one's point of view.

| Year | Source | Archetype | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7th-10th C | Beowulf | unknown | - |

| 1937 | The Hobbit | Goblin/Minion | - |

| 1954 | The Lord of the Rings | Goblin/Minion | introduced stronger Uruk-Hai |

| 1974 | Dungeons & Dragons | mixed | split "goblin" and "orc" |

| 1978 | Advanced Dungeons & Dragons | Raider/Scavenger | added half-orc player race |

| 1982 | Dragons Magazine #62 | Warrior Race | created origin myth |

| 1983 | HârnWorld | Brute/Hoodlum | orcs with insect-like hive society |

| 1987 | Warhammer 40K (miniatures) | Brute/Hoodlum | fungus-related "space orks" |

| 1988 | The Orcs of Thar (Basic D&D) | Raider/Scavenger | made orc an optional player race |

| 1989 | Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (2E) | Raider/Scavenger | removed half-orc player race |

| 1989 | Shadowrun | Brute/Hoodlum | non-evil orcs as underclass in futuristic setting |

| 1993 | Earthdawn | Warrior Race | non-evil orcs as honorable warrior race |

| 1994 | Warcraft (video game) | Warrior Race | initially more pure evil |

| 1999 | Sovereign Stone | Warrior Race | non-evil warriors of the sea |

| 2000 | Dungeons & Dragons (3E) | Brute/Hoodlum | restored half-orc player race, made orcs bigger and green |

| 2001-2003 | Lord of the Rings movies | mixed | changes to make orcs more primitive |

| 2004 | World of Warcraft (MMORPG) | Warrior Race | more honorable in uncorrupted form |

| 2016 | Warcraft (Movie) | Warrior Race | horde invading from other world |

| 2017 | Dungeons & Delvers | other | body-snatching evil spirits like zombies |

| 2024 | Dungeons & Dragons (2024) | mixed | full orc as core PC race, replacing half-orc |

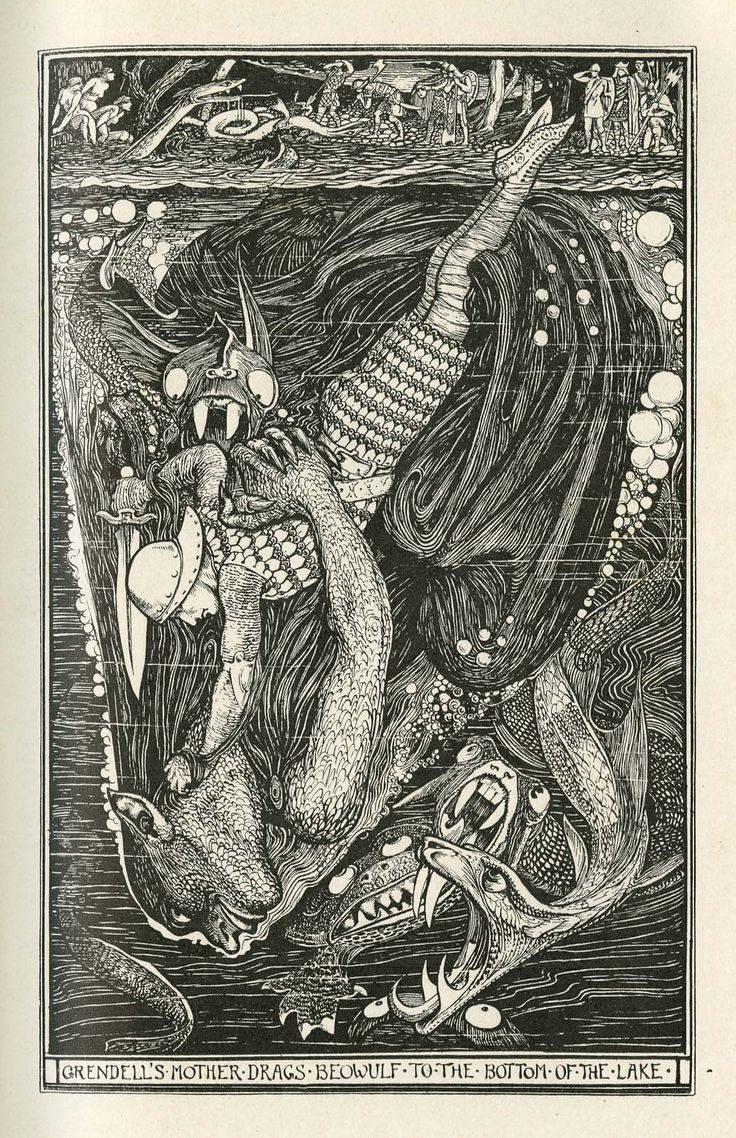

J.R.R. Tolkien created the modern image of orc, but it is worth noting that he took the name from "orcneas" in Old English. This is a medieval type of monster about which little is known, but it is notably mentioned in the epic poem Beowulf. Beowulf is set in pagan Scandinavia in the 5th or 6th century, but it was written in nominally Christian England some time between the 7th and 10th century. In the Francis B. Gummere translation, the word is translated as "evil spirits". (The illustration is an 1899 picture of Beowulf fighting Grendel's mother, not necessarily representing orcneas.)

|

Grendel this monster grim was called, march-riever mighty, in moorland living, in fen and fastness; fief of the giants the hapless wight a while had kept since the Creator his exile doomed. On kin of Cain was the killing avenged by sovran God for slaughtered Abel. Ill fared his feud, and far was he driven, for the slaughter's sake, from sight of men. Of Cain awoke all that woful breed, Ettins and elves and evil-spirits, as well as the giants that warred with God weary while: but their wage was paid them! |

Wæs se grimma gæst Grendel haten, mære mearcstapa, se þe moras heold, fen ond fæsten; fifelcynnes eard wonsæli wer weardode hwile, siþðan him scyppend forscrifen hæfde in Caines cynne. þone cwealm gewræc ece drihten, þæs þe he Abel slog; ne gefeah he þære fæhðe, ac he hine feor forwræc, metod for þy mane, mancynne fram. þanon untydras ealle onwocon, eotenas ond ylfe ond orcneas, swylce gigantas, þa wiðgode wunnon lange þrage; he him ðæs lean forgeald |

This defines orcneas as a sort of monster awakened by the first sin of murder by Cain. They are in the same category as ettins and elves, as well as the monster Grendel and his mother. "Eotenas" or "ettin" is the same root as "jotun", describing the Norse race of giants. "Ylfe" or "elf" is also a Nordic mythological race. Grendel is usually considered human-like in form, but his mother's nature is disputed. She is sometimes depicted as more of a monster or even a dragon, but she might be just a fighting woman bent on revenge for her son.

Neither Beowulf nor other sources offer any description of the "orcneas". Tolkien discovered two "glosses" in other Old English manuscripts - which are notes in the margins for the scribes - indicating that "orc" might mean "þyrs" (ogre) or "heldeofol" (hell-devil). The "neas" means body or corpse. There is also a related term "orcen" for a sort of sea monster, which is the root for modern-day orca (aka killer whale) - though Tolkien rejected this association.

We cannot say for sure how Dark Ages English people pictured orcneas, but the associations can inspire the imagination to possibilities. "Orcneas" could mean "devil-corpse" or it could be "embodied sea monster". They could originate in Christian sin, or they could represent Norse mythological belief.

Tolkien also used "goblin" to describe the same creatures as orcs in his works. The term "goblin" is a broad term for all sorts of evil or mischievous spirits in English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish folklore. They could range in types, like:

The earliest usage of "gobelin" is from Normandy in France, in the writings of 12th century monk Orderic Vital. He described "gobelin" as a demon that lived in the region of Évreux, that was prevented from causing harm by the power of Saint Taurin. This was probably related to local Breton nature spirits or fairies called a "korrigan" who were associated with raised stones and ancient tombs.

Goblins, then, were mostly small spirits who were mischievous and sometimes (but not always) evil. They might do good work like making shoes or cleaning corners, but could also be harmful or even murderous.

Tolkien has creatures called both orcs and goblins. They are material beings created by the evil godlike being Morgoth, who made them as a twisted version of Tolkien's elves. Whereas in Beowulf, elves and orcs both originate from Cain's sin, Tolkien makes his orcs/goblins the polar opposite of his elves. Elves are immortal and beautiful and tall and wise, while orcs/goblins are small and short-lived and ugly and evil.

Tolkien's vision of evil was especially influenced by his time in the trenches of WWI, as well as the destruction of England's forests by industrialization. His orcs/goblins are emblematic of military-industrial war, and he describes orc/goblin industry in The Hobbit:

They make no beautiful things, but they make many clever ones. They can tunnel and mine as well as any but the most skilled dwarves, when they take the trouble, though they are usually untidy and dirty. Hammers, axes, swords, daggers, pickaxes, tongs, and also instruments of torture, they make very well, or get other people to make to their design, prisoners and slaves that have to work till they die for want of air and light. It is not unlikely that they invented some of the machines that have since troubled the world, especially the ingenious devices for killing large numbers of people at once, for wheels and engines and explosions always delighted them, and also not working with their own hands more than they could help; but in those days and those wild parts they had not advanced (as it is called) so far.

This clearly connects orcs/goblins to modern industrialization and war. They are violent and fractious, often fighting with each other unless controlled by a strong master. They speak in cockney mannerisms, like the urban poor of London. However, they are not technologically primitive. They build, maintain, and use sophisticated war machines. They chop down forests to build and fuel great factories for Saruman, and use a kind of bomb to blow up defenses at Helm's Deep. They also have medicine which effectively cures wounds, though it leaves a permanent scar on Merry when used.

Tolkien wrote little about the lives of orcs outside of war. They are described as having been "bred" by Morgoth as well as by Sauron and Saruman. However, Tolkien was reluctant to show mothers or children anywhere in his stories, even at the homes of the good characters. The only reference to orcs growing is that Gollum is described as killing a "small goblin-imp" that squeaked. Orcs presumably have women and children, but that is the only mention. Their age also isn't clear, but based on the appendices they can live for a while. The leader Bolg, son of Azog, is over 140 years old in The Hobbit. Tolkien privately had a note that orcs are short-lived compared to "Men of higher race" - but that's not necessarily a contradiction since some of his humans can live a long time. Aragorn lived to age 210, for example.

Tolkien also mentions half-orcs, including those "bred" by Saruman in the Third Age. It's possible they were created by magically influencing humans to be more orc-like, as opposed to true interbreeding. Still, their similarity to humans is close enough, and they live and fight alongside some humans.

Geographically, in The Lord of the Rings, orc armies gather in Mordor to the East, but more of them can be found all over the map -- including in the far North, and in the central Misty Mountains.

Orcs are physical appearance is also a little unclear. Most orcs are smaller than humans, but a few are up to humans sized - particularly the Uruk Hai that Saruman bred. They are said to have claws, and are hairy and "swart". (A word similar to "swarthy" meaning dark-skinned, usually used for Mediterranean peoples like Spanish or Italians.) The whole description was unclear enough that in the 1950s, a potential film-maker suggested orcs with beaks and feathers. In a letter about the proposal (#210), Tolkien said orcs should instead look more human but degraded, repulsive, and ugly - suggesting they appear like "least lovely Mongol-types".

That description of ugliness showed prejudice, similar to common stereotypes in Tolkien's time of "Mongo" or "mongoloid". Still, his orcs have a mix of real-world influences more than this description, which doesn't appear in his published books. Their cockney speech and clever/cruel machines don't fit Mongol stereotypes, for example.

Tolkien famously argued against symbolism or allegory in stories. Even so, there are clear parallels in his work to many real-world races and cultures - as he has even attested to in letters and interviews. See "The Progress of Tolkien's Dwarves" as an example of his developed meaning. Tolkien was very affected by his experiences in World War I, when he was in the trenches fighting German forces. His orcs are representative more of this evil - the ugliness of war within Europe, and of industrialization as shown in the destruction of forests for war factories.

The orc's cockney speech fits with the real-world people most likely to be conscripted to work in factories or march in armies. There were many negative stereotypes of the "criminal classes" from Victorian eugenics, which this arguably propagates. It also relates to Tolkien's environmentalist themes opposing the military-industrial complex of his time, though.

As to their morality -- Tolkien's orcs are certainly evil, but there are also variations among them in motivation, behavior, and biology. In his letter #153 (from The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien), Tolkien discusses their creation and moral status.

But if they 'fell', as the Diabolus Morgoth did, and started making things 'for himself, to be their Lord', these would then 'be', even if Morgoth broke the supreme ban against making other 'rational' creatures like Elves or Men. They would at least 'be' real physical realities in the physical world, however evil they might prove, even 'mocking' the Children of God. They would be Morgoth's greatest Sins, abuses of his highest privilege, and would be creatures begotten of Sin, and naturally bad. (I nearly wrote 'irredeemably bad'; but that would be going too far. Because by accepting or tolerating their making – necessary to their actual existence – even Orcs would become part of the World, which is God's and ultimately good.)

So they are corrupted and thus evil, but not irredeemable. There are no good orcs described, but one of the core themes of Tolkien's trilogy was mercy for those corrupted by evil -- as exemplified by Gollum/Smeagol. Gollum never became a good person, but it is implied that his redemption was possible. Orcs never had a detailed character like Gollum, however. There are only eight named orcs in Lord of the Rings, and they only appear for short scenes.

Of course, there are many more in-depth questions about orcs in Tolkien, and there is a lot of ambiguity. There are many possible critiques of Tolkien's orcs related to racism or classism. At least, his orcs aren't simple. They are closest to the Goblin/Minion category of archetypes, but they also have organized and fought for themselves - like in The Hobbit.

Peter Jackson's movie adaptations of Lord of the Rings were released from 2001 to 2003, and they have been very important to how Tolkien is visualized. This is well after D&D and other media had their own portrayal of orcs, but I discuss it first because it's important to understand differences between the books and the movies. Some notable changes from the books to the movies were:

In all, this shifts the movie orcs partly towards more inhuman and primitive Brute/Hoodlum as opposed to the military-industrial Goblin/Minion archetype of the books.

The Lord of the Rings was published in 1954, and quickly became massively popular. It was a primary inspiration for Dungeons & Dragons in the early 1970s, by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson. In the 1974 original game twenty years later, orcs and goblins are described as different creatures (unlike Tolkien). More importantly, their place in the world was much different.

Tolkien's orcs/goblins are a powerful force in Middle Earth, raising an major army in The Hobbit and nearly conquering the world in Lord of the Rings. In D&D, orcs and goblins are encountered in isolated bands and are considered minor threats even for weak beginning adventurers.

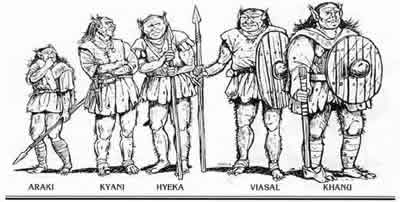

The original 1974 rules barely describe orcs and goblins, beyond their stats and lairs. Orcs live in a "cave complex" (with sentries) or "village" (with ditch and pallisade defense), with mention of "inter-tribal hostility". Curiously, Gygax describes that his earliest D&D players would subdue and conscript orcs to fight for them, and Rob Kuntz even had an "orc hero" as a sidekick. (see "The First Orc Hero") In the 1977 Monster Manual for Advanced Dungeons & Dragons, orcs have a unique look of pig-faced humanoids, while goblins are smaller with tusks but no snout. Among the distinctions from Tolkien:

Thematically, this was a notable shift from Tolkien's military-industrial foot-soldier orcs with fiendish machines (Goblin/Minion) into orcs as standalone primitive raiders (Raider/Scavenger).

The Monster Manual also described half-orcs as being common, described as "unsavory mongrels" mixed with goblins, hobgoblins, and humans particularly. These are said to be "basically orcs", though a rare few can pass as non-orc. This was important because the next year (1978), the Player's Handbook introduced half-orc as one of the core player character races.

Having half-orcs be a race that gamers could choose to play was significant. Even though orcs and half-orcs in general were evil, it was explicitly possible for a half-orc to be a virtuous hero. Later, in Unearthed Arcana (1985), Gygax also made evil dark elves (drow) into a player character race. That was the first full-blooded monster race to be made playable.

Orcs went through a notable re-imagining over the course of RPGs in the 1980s and 1990s. They went from being foot-soldiers and lowly henchmen into being a force of their own. This was helped on by wargames and video games that featured orcs as an independent faction.

The first seminal change came in 1982 with articles by D&D staff writer Roger Moore in Dragon Magazine #62. Moore invented an orc origin myth, and added a pantheon as well as more details on half-orcs. The origin myth went:

In the beginning all the gods met and drew lots for the parts of the world in which their representative races would dwell. The human gods drew the lot that allowed humans to dwell where they pleased, in any environment. The elven gods drew the green forests, the dwarven gods drew the high mountains, the gnomish gods the rocky, sunlit hills, and the halfling gods picked the lot that gave them the fields and meadows. Then the assembled gods turned to the orcish gods and laughed loud and long. “All the lots are taken!” they said tauntingly. “Where will your people dwell, OneEye? There is no place left!”

There was silence upon the world then, as Gruumsh One-Eye lifted his great iron spear and stretched it forth over the world. The shaft blotted out the sun over a great part of the lands as he spoke: “No. You lie. You have rigged the drawing of the lots, hoping to cheat me and my followers. But One-Eye never sleeps; One-Eye sees all. There is a place for orcs to dwell . . . here!” With that, Gruumsh struck the forests with his spear, and a part of them withered with rot. “And here!” he bellowed, and his spear pierced the mountains, opening mighty rifts and chasms. “And here!” and the spearhead split the hills and made them shake and covered them in dust. “And here!” and the black spear gouged the meadows, and made them barren.

“There!” roared He- Who-Watches triumphantly, and his voice carried to the ends of the world. “There is where the orcs shall dwell! There they shall survive, and multiply, and grow stronger, and a day shall come when they cover the world, and shall slay all of your collected peoples! Orcs shall inherit the world you sought to cheat me of!”

This was popular with many D&D fans, and it is intriguing as it portrays the other gods as bullies and Gruumsh as righteous. Nevertheless, orcs are still the warmongering opposition looking to take over the world. This portrays D&D orcs more as a proud warrior race, rather than minions.

Another step in this was the 1988 supplement for the Basic D&D line, "The Orcs of Thar" by Bruce Heard. There, orcs are one of the optional player character races, with varying stats and alignment. The orcs there are violent as well as comical, but also had some added variety and depth.

Whether proud and/or comical, orcs were established more as an angry, primitive, atavistic archetype.

At around the same time, in the miniatures wargame "Warhammer 40K", orcs were re-imagined as a comically violent "space orks", also known as "greenskins". In lore, they are described as mixing features of both animals and fungi. They are sexless and reproduce by releasing spores that grow in the ground into fully adult orks. Further, killing a space ork releases its spores, so they are an ever-growing horde. This neatly avoids the ethical problem of ork babies, and further makes orks into an existential threat based on their fast and unstoppable reproduction.

Their somewhat comedic mannerisms and outfits have been said to draw on stereotypes of European football hooligans, though some have countered that they were more based more on biker gangs and/or 1980s punks. Their war crusades are called "WAAAGH!" -- part of their "kultur" -- and they have a sort of magic or psychi field based on sheer belief. They build ramshackle unworkable technology like ships, but because they believe it can fly, it does.

These orks are also more hulking and powerful-looking, compared to the pig-faced orcs of AD&D. Warhammer 40K was not originally a role-playing game, but it did have orks as a force that players might specialize in and identify with. With players taking orks as their side, it became more important that orks be fun and funny to play, rather than just being henchmen and/or cannon fodder.

Thematically, they represent a satire of tough-guy stereotypes like football hooligans, biker gangs, and pub brawlers. Especially as a wargame, though, the satirical side may get lost in just playing into those stereotypes.

Shadowrun was released in 1989 as a crossing of tropes from D&D with cyberpunk fiction. In the near future of our world, magic awakens and many people transform into "metahumans" including orcs, technically called "homo sapiens robustus". They have big and hairy with tusks, and breed prolifically with short lifespans. They are not particularly evil, but their stat modifiers mean they are a little less intelligent and charismatic than humans. The following is the in-character intro for the "Ork Mercenary" archetype:

What'cha staring at, chummer? Ain't ya never seen a live Ork before? Sure you have. Everyone's seen us. I guess you could say we sort of stand out in a crowd. Ease off on the baby talk, chummer. Just cause I'm Ork don't mean I'm an idiot. I got brains, and I use em, too. Wouldn't be here if I didn't.

So don't ya go giving me none of your sorry eyes. It ain't been no easy life dodging the Badge, but I'm still here staring you in your pasty face. Like all Orks, I'm a survivor. Ain't nothin' or nobody too tough for me, chummer.

So's you want to hire me? Could be that I'm available. That is, if my services ain't in demand elsewhere. Slot your credstick in my box and let's see. If it shows enough zeroes in the right place, you got yourself some muscle.

Commentary: The Ork Mercenary is hardly an advertisement for the gentler side of his metahuman race. He is coarse and rough and of limited sensibilities, but he does function in society. He is not a psychotic criminal as some Humanis cultists claim. He's just making a living doing what he does best.

This is clearly a metaphor for an underclass. Shadowrun intentionally put D&D stereotypes into the modern world, while also adding in elements including a successful Native American rights movement powered by the re-awakened magic, including "shaman" and "tribesman" among the archetypes.

These play into many stereotypes, but they are also highlight underclass and indigenous population far more than prior RPGs.

Shortly thereafter, the Warcraft franchise started as a video game in 1994 entitled "Warcraft: Orcs & Humans". It would go on to have two sequel videos games, a wildly successful MMORPG (massively multiplayer online role-playing game), a tabletop RPG adaptation, and a 2016 movie. For a period in the 2000s, the MMORPG was significantly more popular than D&D, so the archetype from here was quite influential - especially because orcs were at the core of the game's conflict.

Orcs in Warcraft are a relatively primitive species from a dying world (Draenor), who are lead by evil warlocks to invade the human world of Azeroth. They are described as originally having been a "shamanistic society" - and they eventually returned to their original magics. They dress in furs and use more primitive technology.

Even so, orcs here are not just opponents. Starting from the first video game, orcs were intended to be a fun side to play as - with tactical depth and varied options. Originally they were dominated by evil warlocks using a form of magic called "Fel" that was based on sacrifices. These orcs had green skin, tainted by the magics. In Warcraft III (2002) and World of Warcraft (2004), many orcs broke free of the Fel, and returned to their shamanistic roots. In all the games, orcs have been a popular option to play as.

In the 2016 Warcraft movie, five of the ten main cast are orcs. The story begins with an orc chief Durotan bringing his pregnant wife Draka with him into the new world that the evil warlock Gul'dan leads them to invade, along with his second-in-command Orgrim and the half-orc prisoner Garona.

So the Warcraft orcs on the one hand cement orcs as a proud but primitive warrior race - and keep a partial association with evil via the Fel. However, they also set up orcs as protagonists with agency who in some cases heroically fight on the side of good, against the Fel. Orcs are intended as a fun player character race.

Warcraft also highlighted female orcs much more than previous works. Warhammer orks are genderless, and while technically present in Tolkien, D&D, and Shadowrun, female orcs were almost never pictured or in the spotlight. However, female orcs appear regularly as characters in the MMORPG. In turn, the Warcraft movie has two female orcs as major roles, including a pregnant mother. As pictured in World of Warcraft, orc women are muscular, but still look very different from the orc men, who are inhumanly massive and hulking.

Warcraft orcs have a nomadic culture described as "shamanic". They have circular tents and huts, similar to Turkish or Mongol designs. Their Horde allies the Tauren have longhouses and totem poles. These draw on non-European aesthetics, compared to the human-centered Alliance whose aesthetics are generally from medieval Europe -- like European-style castles, manors, and knights.

The later editions of D&D subtlely shifted in a direction similar to Warcraft's "Warrior Race" orcs and Lord of the Rings films.

Smaller RPGs have had a number of variants of orcs over the years. A few notable examples follow.

Hârn is an RPG fantasy setting by N. Robin Crossby that made a remarkably detailed and consistent medieval setting merging influences from Tolkien, D&D, and historical England, first published in 1983. The orcs in Hârn, called "Gargun", which are unique for having a social structure based on insects, even though adult orcs are physically similar to other orcs. They have a hive with only one huge fertile female, who lays a massive numbers of eggs. Hatched orcs are born with common racial memories, grow to full adulthood in one year, and live at most 25 years.

The culture of Gargun is more utilitarian than D&D orcs. They are not particularly primitive, though they are also not particularly advanced.

The orcs were further details in the 1997 supplement "Nasty, Brutish, And Short: The Orcs Of Hârn". One twist it introduced was how orc women are only 1% of births, and they are bigger and tougher than orc men. They are kept separate from the men, and formed an elite "queen's guard". Any of them could potentially become a new queen, but they are loathe to do so because they would become an enormous bloated egg-laying machine.

The curious dynamics of the insect-like social structure makes them unique and interesting.

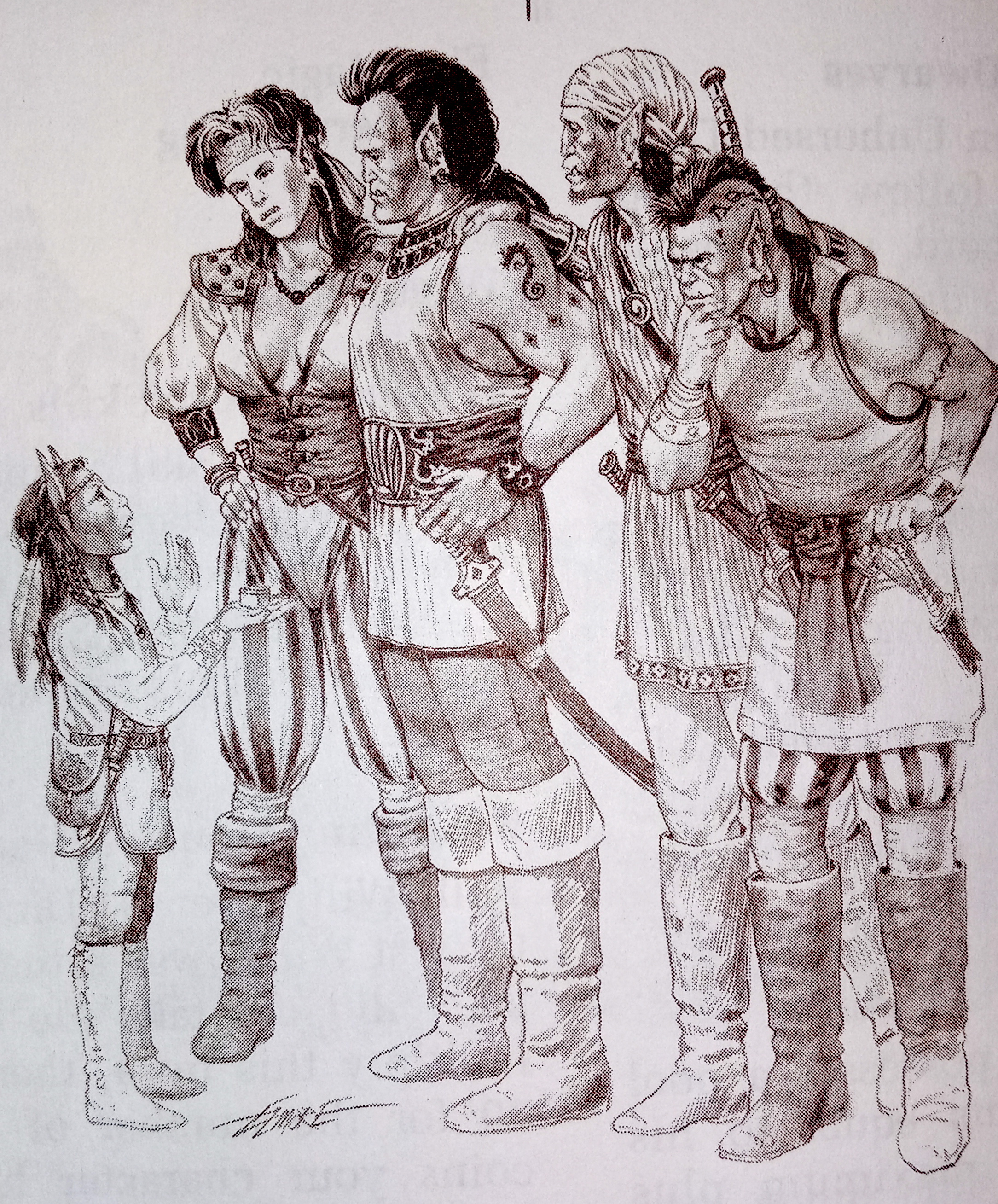

Sovereign Stone is an RPG released in 1999 by Don Perrin and Lester Smith, illustrated by Larry Elmore. It was pitched as an alternative to D&D, at a time when TSR had been acquired after financial mishaps. It imagined a world with variants of the D&D races each with a major break from previous stereotypes.

In the case of orks, they were re-imagined as proud warriors of the sea. This relates back to the etymological connection between "orcneas" and orcas (killer whales). Besides their affinity for the sea, they are inventors and tinkerers - creating siege engines as well as "Flaming Jelly" that no other race has been able to duplicate. Their ships are fast and maneuverable and made for ramming.

These orks are also superstitious and practice shamanistic magic. They offer sacrifices of either their own people or enemies to their sea gods, such as strangling and throwing one into their holy volcano. They also pay careful attention to any omens.

Essentially, these orks play into many pirate stereotypes rather than either the stereotypes of Tolkien or original D&D.

Dungeons & Delvers is pitched as a variant version of traditional Dungeons & Dragons. It is designed to be familiar, with some new mechanics and options. Specifically, it advertises that "many creatures have been tweaked or wholly reimagined both visually and/or mechanically."

In the case of orcs, they were re-imagined as demonic spirits tightly wrapped in the flesh of other races. They are created by the demon lord Orcus, existing to slaughter, offer up the remains of victims as sacrifices to Orcus, and using the leftover skins to summon more orcs into the world. They do not need to eat, drink, breath, or sleep. This connects to the Old English possible meaning of "orcneas" as "devil-corpse", as noted in the Beowulf section.

The author David Guyll specifically came out against the idea the suggestion that evil races are bad game design. Though these orcs are re-imagined such that they aren't even accurately described as a race. Rather, they are more like a merging of modern cinematic zombies with some trappings of orcs.

This eliminates any moral qualms with killing orcs, and makes them more threatening in many ways.

The big question is what else can be done with orcs? They have potential to be interesting as enemies, as a player character race, and as both. Are there other ways to approach them? The following sections detail how orcs were approached in several campaigns.

As noted earlier, it is striking how later interpretations tossed out the military-industrial aspects of Tolkien's orcs, making them technologically backwards and crude, rather than cruelly clever. This has even influenced many RPG adaptations set in Middle Earth. A true-to-Tolkien adventure could invert this.

I have run a number of games in Middle Earth, using the Savage Worlds rules. One standalone adventure is called "The Dwarven Peace Crusade", and is set a century before The Hobbit, during a great war between dwarves and orcs.

I added a possible encounter with a group of wounded dwarves, who had relied on captured orc medicine which despite its scarring is better than the medicine they have. I also describe the scenes of previous battles to include the war machines that the orcs had.

The point is to emphasize the contrast between orcs who shrug off war without consequence, and those who grow weary and grieving from the losses of war.

"Land of New Horizons" is a homebrew setting for D&D developed by my son Milo Kim and myself. It is intended to use all the core D&D races, classes, and features - but reinterpret them all in the context of a fantasy world inspired by Incan mythology and history, as well as other Andean cultures. In it, there are four races that founded the Solar Empire:

So here orcs are still shown as warlike, but they are considered righteous and holy warriors for the empire, whose king is divinely appointed by the Sun God. In the world, some suggest that without the leadership and culture of the empire, that orcs might fall to evil and plundering. But as things are, they are the proud and honorable troops of the empire.

This retains most of the features of orcs as a race, while it also works against many stereotypes about Native Americans in general and the Incans in particular. Having all four races be core to the empire emphasizes the diversity among the Incans, when the common stereotypes lump all Native Americans together.

In particular, the scope and martial might of the Incans is often overlooked. The Incan Empire at its height was as large as the Western Roman Empire, encompassing people of many languages and ethnicities. Having both orcs and elves be Incan emphasizes their diversity as well as their martial prowess.

The City of Haven was a GURPS Fantasy campaign, set in a world where humans, dwarves, and orcs were the core races. Elves were a barely-accepted fringe because they had once ruled the world with powerful magics, until a catastrophic collapse ended their reign. Halflings were a little-known and wild race who appeared only after the catastrophe.

As a player in this setting, I had created my orc PC Ufthak as the son of a rich arms merchant. I took as my model the stories of modern crime families like "The Sopranos". So my PC was an educated and privileged rich young man, who ostensibly was an expert in crafting and selling arms, but was also capable of being a shady gangster as was his roots.

This also keeps many aspects of orc archetypes while also driving into new territory. What happens when some orcs are successful and rich?

"Out from the Temple" was a one-shot adventure and later a short campaign I ran, which was a reversal of original D&D races. I used material from the classic module "The Temple of Elemental Evil", but in this world, orcs and other humanoids are the good races, and humans, elves, dwarves, and their allies are evil races.

In doing this, I took key traits of the humanoids but removed the evil association. In the case of orcs, I gave this description:

Your people, the orcs, have always lived simply and plainly. They work hard and shun the fancy trappings of other races. An orcish tool will never be as beautiful as drow handiwork, but it will do its job dependably. Orcs till the soil and make a living even in places that other races avoid as wastelands. The elves have their green forests, the dwarves the rich mountains, and the gnomes their fertile hills. Meanwhile, orcs make a simple living in among trackless jungle, treacherous crags, and barren rocky fields.

This builds from the mythology of D&D orcs, but makes them as salt-of-the-earth farmers who till the soil to make a working home out of difficult lands. In the adventure, the PCs were on a quest to find and restore the lost Temple of the Elements. It had been a great temple of good, but it was attacked and killed by evil humans.

In fairness, I abandoned this setting because I felt like even though players had fun, it did not fully hang together for me. In the short campaign, one of the players had trouble with humans being purely evil, and tried to engage in diplomacy with them - which naturally failed. This showed failure to engage with the premise, though. Still, it was an interesting experiment to have tried.

I hope that the overview and case studies show the range of possibility that orcs can represent, beyond the lowest common denominator. The message of orcs depends on the context in which they appear.

A common criticism of orcs centers on bioessentialism - the idea that genetic differences are important to life and to how history turned out. So, for example, Europeans conquered much of the world, which is fairly objective history. Bioessentialism would attribute this to something in the European genetic makeup, as opposed to other factors or circumstances. Especially, bioessentialists often suggest great differences among traditional race classifications, like white, black, Asian, and Native American.

Fantasy races goes farther than real-world bioessentialism. i.e. Orcs really are innately better at war than halflings. Gnomes really are innately better at math than humans. Some would say that this promotes real-world bioessentialism.

I don't discount that this could be the case. There have been racist stereotypes of black people (or other races) as a primitive savage horde attacking civilized white people. The 1925 story "The Last White Man", by Robert E. Howard, is a good illustration these stereotypes. Without delving into specific products, orcs could definitely echo these stereotypes.

However, as I mentioned in discussion of "Land of New Horizons", using fantasy races can also play against some stereotypes. In that setting, having elves and orcs both be founders of the Inca-like Solar Empire works to counter stereotypes that lump all Native Americans together. They also conveys the Incan Empire's diversity as well as its exquisite craftsmanship and its martial might. If the same game were done with only humans, the Solar Empire would seem less fantastically diverse.

Here, the fantasy differences aren't just incidental. They actively promote a message that goes against the stereotype. This shows how the context determines how the fantasy relates to reality. Conversely, especially military-industrial orcs close to Tolkien's originals could be thematically used to embody evils of imperialism and slavery.

More generally, it's important to understand that any given fantasy is only one picture. Myths are like parables. Any given myth doesn't say about how all reality should be. Rather, it has at most a few lessons about specific moral points.

Medieval fantasy often clashes democracy, freedom of speech, and true egalitarianism. However, the magic is often lost if we try to engineer our fantasy to have all our modern values.

For example, in the Haven example, the rich orc clans were modeled on mobsters -- like the Sicilians, Russians, or Irish. That could lean into negative ethnic stereotypes, but it could also be positive exploration.

The Land of New Horizons example is in some sense pro-imperialism and pro-authoritarianism, since it pushes a divinely-appointed emperor as true moral good. This exaggerated view isn't intended to be right, but it brings an Incan point of view -- just as European mythic figures like King Arthur and Charlemagne convey a positive view of their history.

None of this is a prescription. I think this essay shows some of the variety of orcs and what they can represent, but no one is obliged to use any of these. Come up with something completely different, or only use one type ever, or don't use orcs at all. What they represent will depend on how they are portrayed, and there is great variety in that.

In order of publication date